The Gist of the Rock Animation

How and why I made Organima: The Dodeda

A look at a stone species that has lost count of time. Animation by Nik Arthur, rock-solid sound by Will Miller.

Two young dodeda are playing when they’re approached by an older dodeda, an elder. This ancient dodeda initiates a connection, reaching out a vein from each of its rings to make contact. It then migrates a shadow its life’s memories to the younger one; a great honour, as it can be done only once. Once completed, the elder accepts its 7th ring, which is the final ring for a dodeda. This last ring prompts the rebirth transition, where the elder reintegrates itself back into the stone, leaving behind 3 newly born dodeda, safe in the rubble.

I wanted to animate with rock, so I spent a few months figuring out how to. The final result is a short animation featuring a culture of creatures that live on the surface of stone, a sacred rebirth ritual, and the joy of friends playing. At a glance this may be a tad difficult to read. Because really, the animation is just circles moving around a rock; they whip around and natural blues and oranges light up the stone backdrop. It’s pretty, and that’s great! People like pretty content. But something has to inform how these circles move, otherwise it’d be a bit of hollow. A hollow rock is not a strong one. It would be random, like a Cool Visualizer, (which I’m well versed in). So I found these small creatures that tell a story about life in stone.

Convincing someone of an animation is about believability, more so than reality or even creativity. Richard Williams, a renowned animator and author of The Animator’s Survival Kit, (which I haven’t read), said “What we want to achieve isn’t realism, it’s believability.” This quality in animation - believability - is what makes things feel right. When animation is taking place on a real material, not the ‘blank slate’ of paper, that goal of believability influences not only the animation style, but the technique and process. So, what feels right on a rock?

I try to work with natural materials naturally. When I’m working with a specific substance I often try to avoid adding other foreign elements to it, for it is usually rather unnatural, or feels kind of wrong. The stone doesn’t want any gunk sitting on top of it, it wants to be a stone. To animate the dodeda, I engraved into a small slab of rock, making marks by carving grooves, much like the effect of natural weathering of stone or like the ancient petroglyphs. This felt like the most sensible way to go about animating with stone— by just subtracting from what is already there, rather than adding some gunk on to the surface. It felt natural. What’s important when finding out what feels natural, is taking a look around, and listening closely. This can be done on a walk, in a book, or even just on wikipedia. Maybe you will find the patterns of slime mold covering stones, and in that case, maybe they do want some gunk on them. Maybe you will find petroglyphs. For me, to base decisions on what feels the most natural is to see how things happen either without human interference, or how we’ve been interfering with these elements through history. That way to us, when we see it, it feels like it belongs.

So, if I want you to believe in a culture of creatures on stone, I need to present them to you in a way that feels right. Carving characters into the stone itself feels natural, they feel as though they belong there, and you can become immersed.

You have to be ready to be shoved around a little when working with natural substances— these pushes can be unbalancing, and the easiest way to fall over is by fighting-against rather than moving-with. I used a rotary drill and sanding discs to engrave each animation frame, and grind them away after scanning. Due to the grinding, the rock’s stature slowly shrunk as we moved together through the animation. (I really got the better bargain from this collaboration— all I gave up was a hundred hours at my studio, whereas my rock companion gave up its sediment). As sanding pads wore down, they would polish the rock, bringing out blacks and blues and oranges (these didn’t really show up to the eye, just the scanner). At the beginning, these marks were showing up as dark blotches, and the sanding pad was leaving these brush-like streaks. Oh god, how ugly! I thought. I desperately tried to erase them, but they would not leave. I panicked, looked for a new rock, found one, it failed, and I was back to my blotchy first rock. I continued onward, and gradually started working with these new marks in mind, and found how they can be used to emphasize movements or build tension. It now seems obvious to me that they should be embraced and not run from, they are after all a natural byproduct of the process. Of course they are the favourite part to everyone I’ve shown.

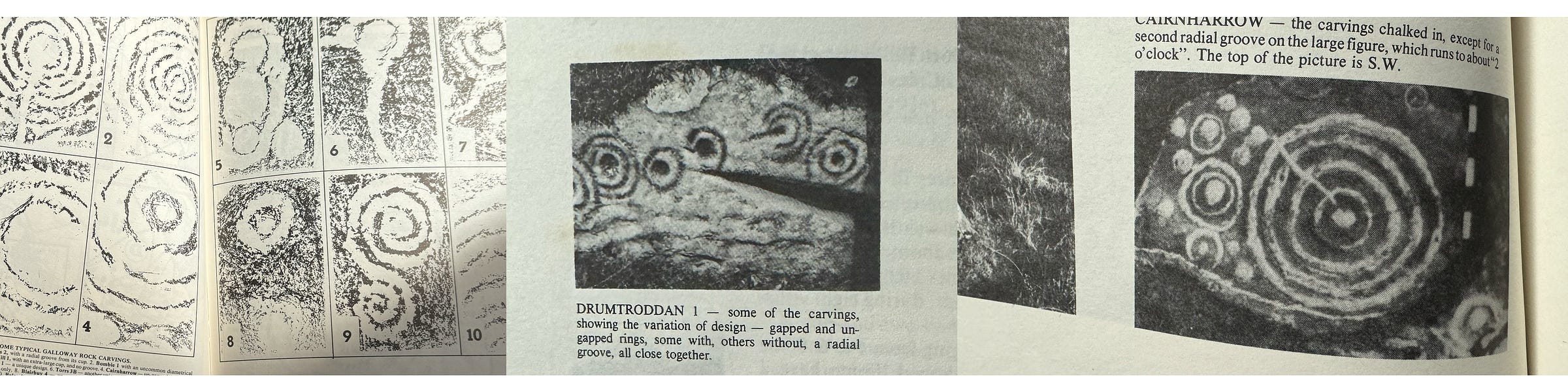

I found the dodeda in a book called The Prehistoric Rock Art of Galloway and the Isle of Man, by Ronald W. B. Morris. They were all over, populating almost every page. Well, photos of them were. They actually populate hundreds of rocks and stone faces all over the world, though mostly in Scotland. The book lists 104 theories as to what these markings mean, ranging from communications between groups of early humans to drawings of breasts. It was pretty clear to me what these markings were.

The dodeda. Comprised of an inner cup (dot) with between 1 and 7 outer ringers encircling it, the dodeda play, share, live and die with a jagged-like fluid motion on stone. Their biome is harsh and long, so they are tough and patient. On the surface of rock elapsed time makes little sense, so the dodeda are practically ageless. But they still mature through their own life cycle, which happens in 7 stages. Dodeda form new rings throughout their life during key moments of growth, like developing a sense of self and making sacrifice for community. Upon accepting their 7th and final ring, they return to the stone and leave behind new life in the rubble.

And, as we’ve established, they’re some circles I drew on this rock I found.

This is, very strictly speaking, very childish. Maybe getting your hands on a Dremel and grinding stone can feel sort of ‘adult’, but taking a culture of rock creatures quite seriously is something a child would do. The childhood imagination is a vibrant and treasured force that must be suffocated as soon as we catch a whiff of the sour fruits of teenagehood. My childhood friend and I used to pick petals from our mothers’s gardens and assemble dishes which we called fairy food, obviously for the local fairies. We’d leave them in the uplifted, gnarled roots of a hundred year old oak tree, where squirrels and other smart animals surely enjoyed them before any mystical creatures could. Funnily enough, they cut the old oak down around the same time I was shoo-ing away my inner child, so I only felt the slightest pang of sadness. This organima project I’m doing is an effort to welcome back some childishness, because they are hearing something in the world that we are not, because they are listening.

-na